what happened to the frankish empire after charlemagne died

| Carolingian Empire | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800–888 | |||||||||||||

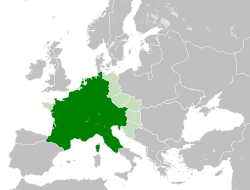

The Carolingian Empire at its greatest extent in 814

| |||||||||||||

| Capital letter | Metz,[1] Aachen | ||||||||||||

| Mutual languages | Latin (official) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Empire | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Eye Ages | ||||||||||||

| • Coronation of Charlemagne | 800 | ||||||||||||

| • Division after Treaty of Verdun | 843 | ||||||||||||

| • Expiry of Charles the Fat | 888 | ||||||||||||

| Surface area | |||||||||||||

| [2] | i,112,000 km2 (429,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

| •[2] | x,000,000–20,000,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Denarius | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and primal Europe during the early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and equally kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo 3 in an endeavour to transfer the Roman Empire from eastward to w. The Carolingian Empire is considered the get-go phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire, which lasted until 1806.

After a ceremonious war (840–843) following the death of Emperor Louis the Pious, the empire was divided into autonomous kingdoms, with one male monarch still recognised as emperor, but with footling authority outside his own kingdom. The unity of the empire and the hereditary right of the Carolingians connected to be acknowledged. In 884, Charles the Fatty reunited all the Carolingian kingdoms for the terminal time, simply he died in 888 and the empire immediately split up. With the simply remaining legitimate male of the dynasty a child, the nobility elected regional kings from outside the dynasty or, in the case of the eastern kingdom, an illegitimate Carolingian. The illegitimate line continued to rule in the eastward until 911, while in the western kingdom the legitimate Carolingian dynasty was restored in 898 and ruled until 987 with an interruption from 922 to 936.

The size of the empire at its inception was around ane,112,000 square kilometres (429,000 sq mi), with a population of between 10 and 20 million people.[2] Its heartland was Francia, the country betwixt the Loire and the Rhine, where the realm'due south primary purple residence, Aachen, was located. In the south it crossed the Pyrenees and bordered the Emirate of Córdoba and, after 824, the Kingdom of Pamplona; to the north it bordered the kingdom of the Danes; to the w it had a short land border with Brittany, which was after reduced to a tributary; and to the due east it had a long border with the Slavs and the Avars, who were somewhen defeated and their state incorporated into the empire. In southern Italy, the Carolingians' claims to dominance were disputed by the Byzantines (eastern Romans) and the vestiges of the Lombard kingdom in the Principality of Benevento.

The term "Carolingian Empire" is a modern convention and was not used past its contemporaries. The linguistic communication of official acts in the empire was Latin. The empire was referred to variously equally universum regnum ("the whole kingdom", as opposed to the regional kingdoms), Romanorum sive Francorum imperium [a] ("empire of the Romans and Franks"), Romanum imperium ("Roman empire"), or even imperium christianum ("Christian empire").[3]

History [edit]

Rise of the Carolingians (c. 732–768) [edit]

Though Charles Martel chose non to accept the title of king (equally his son Pepin Three would) or emperor (as his grandson Charlemagne), he was the absolute ruler of virtually all of today's continental Western Europe north of the Pyrenees. Only the remaining Saxon realms, which he partly conquered, Lombardy, and the Marca Hispanica due south of the Pyrenees were pregnant additions to the Frankish realms later his decease.

Martel cemented his place in history with his defense of Christian Europe against a Muslim army at the Battle of Tours in 732. The Iberian Saracens had incorporated Berber lite horse cavalry with the heavy Arab cavalry to create a formidable army that had most never been defeated. Christian European forces, meanwhile, lacked the powerful tool of the stirrup. In this victory, Charles earned the surname Martel ("the Hammer").[four] Edward Gibbon, the historian of Rome and its aftermath, called Charles Martel "the paramount prince of his historic period".

Pepin 3 accepted the nomination as king by Pope Zachary in almost 741. Charlemagne's rule began in 768 at Pepin'south decease. He proceeded to accept control of the kingdom post-obit his blood brother Carloman's death, as the 2 brothers co-inherited their father's kingdom. Charlemagne was crowned Roman Emperor in the year 800.[ane]

During the reign of Charlemagne (768–814) [edit]

The Dorestad Brooch, Carolingian-style cloisonné jewelry from c. 800. Establish in the Netherlands, 1969.

The Carolingian Empire during the reign of Charlemagne covered nearly of Western Europe, as the Roman Empire one time had. Unlike the Romans, whose imperial ventures between the Rhine and the Elbe lasted fewer than twenty years before existence cutting short past the disaster at Teutoburg Wood (9 Advertizing), Charlemagne defeated the Germanic resistance and extended his realm to the Elbe more lastingly, influencing events well-nigh to the Russian Steppes.

Charlemagne's reign was i of nearly-constant warfare, participating in annual campaigns, many led personally. He defeated the Lombard Kingdom in 774 and annexed it into his ain domain by declaring himself 'King of the Lombards'. He later led a failed entrada into Spain in 778, ending with the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, which is considered Charlemagne's greatest defeat. He then extended his domain into Bavaria subsequently forcing Tassilo Iii, Duke of Bavaria, to renounce any claim to his title in 794. His son, Pepin, was ordered to campaign confronting the Avars in 795 since Charlemagne was occupied with Saxon revolts. Eventually, the Avar confederation ended in 803 afterward Charlemagne sent a Bavarian army into Pannonia. He likewise conquered Saxon territories in wars and rebellions fought from 772 to 804, with such events as the Massacre of Verden in 782 and the codification of the Lex Saxonum in 802.[4] [5]

Prior to the death of Charlemagne, the Empire was divided amidst various members of the Carolingian dynasty. These included King Charles the Younger, son of Charlemagne, who received Neustria; Male monarch Louis the Pious, who received Aquitaine; and King Pepin, who received Italy. Pepin died with an illegitimate son, Bernard, in 810, and Charles died without heirs in 811. Although Bernard succeeded Pepin as king of Italy, Louis was made co-emperor in 813, and the entire Empire passed to him with Charlemagne's decease in the winter of 814.[6]

Reign of Louis the Pious and the civil state of war (814–843) [edit]

Detailed map of the Carolingian Empire at its greatest extension (814) and subsequent partitioning of 843 (Treaty of Verdun).

Louis the Pious' reign as Emperor was unexpected; every bit the 3rd son of Charlemagne, he was originally crowned Male monarch of Aquitaine at three years erstwhile.[7] With the deaths of his older siblings, he went from 'a boy who became a rex to a human who would exist emperor'.[vii] Although his reign was mostly overshadowed by the dynastic struggle and resultant ceremonious war, every bit his epithet states, he was highly interested in matters of faith. I of the first things he did was 'ruling the people by law and with the wealth of his piety',[eight] namely past restoring churches. "The Astronomer"[b] stated that, during his kingship of Aquitaine, he 'built upwardly the study of reading and singing, and also the agreement of divine and worldly letters, more than quickly than one would believe.'[9] He also made significant effort to restore many monasteries that had disappeared prior to his reign, as well as sponsoring new ones.[7]

Louis the Pious' reign lacked security; he often had to struggle to maintain control of the Empire. As before long as he heard of the death of Charlemagne, he hurried to Aachen, where he exiled many of Charlemagne's trusted advisors, such as Wala. Wala and his siblings were children of the youngest son of Charles Martel, and so were a threat as a potential alternative ruling family.[10] Monastic exile was a tactic Louis used heavily in his early reign to strengthen his position and remove potential rivals.[10] In 817 his nephew, Rex Bernard of Italian republic, rebelled confronting him due to discontent with existence the vassal of Lothar, Louis' eldest son.[11] The rebellion was quickly put down past Louis, and past 818 Bernard of Italy was captured and punished - the penalisation of death was commuted to blinding. Notwithstanding, the trauma of the process catastrophe up killing him two days later on.[12] Italy was brought back into Majestic control. In 822 Louis' show of penance for Bernard'southward death greatly reduced his prestige every bit Emperor to the nobility – some suggest it opened him up to 'clerical domination'.[13] All the same, in 817 Louis had established three new Carolingian kingships for his sons from his first marriage: Lothar was made Rex of Italy and co-Emperor, Pepin was made Rex of Aquitaine, and Louis the German was made King of Bavaria. His attempts in 823 to bring his quaternary son (from his second marriage), Charles the Bald into the will was marked by the resistance of his eldest sons. Whilst this was part of the reason for strife amongst Louis' sons, some propose that information technology was the appointment of Bernard of Septimania as chamberlain which caused discontent with Lothar, as he was stripped of his co-Emperorship in 829 and was banished to Italy (although it is non known why; The Astronomer simply states that Louis 'dismissed his son Lothar to go back to Italy'[14]) and Bernard causeless his place as second in control to the emperor.[ten] With Bernard's influence over not but the emperor, but the empress also, further discord was sowed amongst prominent nobility. Pepin, Louis' second son, too, was disgruntled; he had been implicated in a failed military campaign in 827, and he was tired of his male parent's overbearing involvement in the ruling of Aquitaine.[10] Every bit such, the angry nobility supported Pepin, civil war broke out during Lent in 830, and the last years of his reign were plagued by civil war.

Shortly later Easter, his sons attacked Louis' empire and dethroned him in favour of Lothar. The Astronomer stated Louis spent the summer in the custody of his son, 'an emperor in name but'.[10] The post-obit year Louis attacked his sons' kingdoms past drafting new plans for succession. Louis gave Neustria to Pepin, stripped Lothar of his Majestic title and granted the Kingdom of Italia to Charles. Another sectionalization in 832 completely excluded Pepin and Louis the German, making Lothar and Charles the sole benefactors of the kingdom, which precipitated Pepin and Louis the German revolting in the aforementioned year,[ten] followed by Lothar in 833, and together they imprisoned Louis the Pious and Charles. Lothar brought Pope Gregory IV from Rome under the guise of mediation, but his true role was to legitimise Lothar and his brothers' rule by deposing and excommunicating Louis.[ten] By 835, peace was made within the family, and Louis was restored to the Imperial throne at the church of St. Stephen in Metz. When Pepin died in 838, Louis crowned Charles king of Aquitaine, whilst the nobility elected Pepin's son Pepin II, a disharmonize which was not resolved until 860 with Pepin's death. When Louis the Pious finally died in 840, Lothar claimed the unabridged empire irrespective of the partitions.

As a outcome, Charles and Louis the German language went to war confronting Lothar. After losing the Boxing of Fontenay, Lothar fled to his capital at Aachen and raised a new army, which was inferior to that of the younger brothers. In the Oaths of Strasbourg, in 842, Charles and Louis agreed to declare Lothar unfit for the imperial throne. This marked the east–west division of the Empire between Louis and Charles until the Verdun Treaty. Considered a milestone in European history, the Oaths of Strasbourg symbolize the birth of both France and Germany.[fifteen] The partitioning of Carolingian Empire was finally settled in 843 by and between Louis the Pious' three sons in the Treaty of Verdun.[16]

Later on the Treaty of Verdun (843–877) [edit]

Lothar received the imperial title, the kingship of Italy, and the territory between the Rhine and Rhone Rivers, collectively called the Central Frankish Realm. Louis was guaranteed the kingship of all lands to the eastward of the Rhine and to the n and e of Italy, which was called the Eastern Frankish Realm which was the precursor to modern Frg. Charles received all lands due west of the Rhone, which was called the Western Frankish Realm.

Lothar retired Italy to his eldest son Louis II in 844, making him co-emperor in 850. Lothar died in 855, dividing his kingdom into three parts: the territory already held by Louis remained his, the territory of the one-time Kingdom of Burgundy was granted to his third son Charles of Burgundy, and the remaining territory for which there was no traditional name was granted to his second son Lothar II, whose realm was named Lotharingia.

Louis II, dissatisfied with having received no boosted territory upon his begetter's death, allied with his uncle Louis the German against his brother Lothar and his uncle Charles the Bald in 858. Lothar reconciled with his blood brother and uncle shortly later. Charles was then unpopular that he could not heighten an army to fight the invasion and instead fled to Burgundy. He was only saved when the bishops refused to crown Louis the German king. In 860, Charles the Bald invaded Charles of Burgundy's kingdom but was repulsed. Lothar II ceded lands to Louis Two in 862 for support of a divorce from his married woman, which caused repeated conflicts with the pope and his uncles. Charles of Burgundy died in 863, and his kingdom was inherited by Louis II.

Lothar 2 died in 869 with no legitimate heirs, and his kingdom was divided between Charles the Bald and Louis the German in 870 by the Treaty of Meerssen. Meanwhile, Louis the German was involved in disputes with his three sons. Louis II died in 875, and named Carloman, the eldest son of Louis the German, his heir. Charles the Baldheaded, supported by the pope, was crowned both king of Italy and emperor. The following year, Louis the High german died. Charles tried to addendum his realm too, but was defeated decisively at Andernach, and the Kingdom of the eastern Franks was divided between Louis the Younger, Carloman of Bavaria and Charles the Fat.

Decline (877–888) [edit]

The empire, later the death of Charles the Bald, was under assault in the north and west past the Vikings and was facing internal struggles from Italian republic to the Baltic, from Hungary in the east to Aquitaine in the w. Charles the Bald died in 877 crossing the Pass of Mont Cenis, and was succeeded by his son, Louis the Stammerer as king of the Western Franks, merely the title of emperor lapsed. Louis the Stammerer was physically weak and died 2 years later, his realm being divided between his eldest two sons: Louis 3 gaining Neustria and Francia, and Carloman gaining Aquitaine and Burgundy. The Kingdom of Italian republic was finally granted to King Carloman of Bavaria, just a stroke forced him to abdicate Italy to his brother Charles the Fatty and Bavaria to Louis of Saxony. Besides in 879, Boso of Vienne founded the Kingdom of Lower Burgundy in Provence.

In 881, Charles the Fat was crowned emperor while Louis Three of Saxony and Louis III of Francia died the following year. Saxony and Bavaria were united with Charles the Fat's Kingdom, and Francia and Neustria were granted to Carloman of Aquitaine who also conquered Lower Burgundy. Carloman died in a hunting blow in 884 after a tumultuous and ineffective reign, and his lands were inherited by Charles the Fat, effectively recreating the empire of Charlemagne.

Charles, suffering what is believed to be epilepsy, could not secure the kingdom confronting Viking raiders, and after buying their withdrawal from Paris in 886 was perceived by the courtroom as being cowardly and incompetent. The following year his nephew Arnulf of Carinthia, the illegitimate son of King Carloman of Bavaria, raised the standard of rebellion. Instead of fighting the insurrection, Charles fled to Neidingen and died the following twelvemonth in 888, leaving a divided entity and a succession mess.

Divisions of the Empire [edit]

Division of Charlemagne'south empire in three kingdoms ruled past his grandsons

Carolingian successor state of Heart Francia was divided into 3 kingdoms in 855.

Divisions in 887–88 [edit]

The Empire of the Carolingians was divided: Arnulf maintained Carinthia, Bavaria, Lorraine and modern Germany; Count Odo of Paris was elected Male monarch of Western Francia (French republic), Ranulf Ii became King of Aquitaine, Italian republic went to Count Berengar of Friuli, Upper Burgundy to Rudolph I, and Lower Burgundy to Louis the Bullheaded, the son of Boso of Arles, Male monarch of Lower Burgundy and maternal grandson of Emperor Louis II. The other part of Lotharingia became the duchy of Burgundy.[17]

Demographics [edit]

The study of demographics in the early on Heart Ages is a notably hard task. In his comprehensive Framing the Early Middle Ages, Chris Wickham suggests that there are currently no reliable calculations for the catamenia regarding the populations of early medieval towns.[eighteen] What is likely, however, is that most cities of the empire did non exceed the 20–25,000 speculated for Rome during this period.[18] On an empire-wide level, populations expanded steadily from 750 to 850 AD.[19] Figures ranging from 10 to 20 1000000 accept been offered, with estimates being devised based on calculations of empire size and theoretical densities.[20] Recently, however, Timothy Newfield challenges the idea of demographic expansion, criticising scholars for relying on the impact of recurring pandemics in the preceding menstruation of 541-750 AD and ignoring the frequency of famines in Carolingian Europe.[21]

A study using climate proxies such equally the Greenland Ice cadre sample 'GISP2' has indicated that there may have been relatively favourable conditions for the empire's early years, although several harsh winters appear afterwards.[22] Whilst demographic implications are observable in contemporary sources, the extent of the bear upon these findings on the empire's populations is difficult to discern.

Ethnicity [edit]

Studies of ethnicity in the Carolingian Empire have been largely limited. Still, it is accepted that the empire was inhabited by major indigenous groups such as Franks, Alemanni, Bavarians, Thuringians, Frisians, Lombards, Goths, Romans and Slavs. Ethnicity was merely 1 of many systems of identification in this period and was a manner to bear witness social status and political agency. Many regional and ethnic identities were maintained and would later on go significant in a political function. Regarding laws, ethnic identity helped determine which codes applied to which populations, however these systems were not definitive representations of ethnicity as these systems were somewhat fluid.[23]

Gender [edit]

Evidence from Carolingian estate surveys and polyptychs appears to suggest that female person life expectancy was lower than that of men in this period, with analyses recording high ratios of males to females.[24] Yet, it is possible this is due to a recording bias.

Government [edit]

The authorities, administration, and organization of the Carolingian Empire were forged in the courtroom of Charlemagne in the decades around the yr 800. In this year, Charlemagne was crowned emperor and adjusted his existing royal assistants to live up to the expectations of his new title. The political reforms wrought in Aachen were to take an immense impact on the political definition of Western Europe for the residuum of the Middle Ages. The Carolingian improvements on the old Merovingian mechanisms of governance have been lauded by historians for the increased central command, efficient bureaucracy, accountability, and cultural renaissance.

The Carolingian Empire was the largest western territory since the fall of Rome, but historians accept come to doubtable the depth of the emperor'southward influence and command. Legally, the Carolingian emperor exercised the bannum, the right to dominion and command, over all of his territories. Also, he had supreme jurisdiction in judicial matters, made legislation, led the regular army, and protected both the Church and the poor. His administration was an try to organize the kingdom, church, and dignity effectually him, nevertheless, its efficacy was directly dependent upon the efficiency, loyalty and support of his subjects.

Military [edit]

Almost every year betwixt the accession of Charles Martel and the conclusion of the wars with the Saxons Frankish forces went on campaign or trek, often into enemy territory.[25] Charlemagne would, for many years, gather an assembly around Easter and launch a armed services effort that would typically take place through the summertime as this would ensure in that location were enough supplies for the fighting forcefulness.[26] Charlemagne passed regulations requiring all mustered fighting men to own and bring their own weapons; the wealthy cavalrymen had to bring their own armour, poor men had to bring spears and shields, and those driving the carts had to have bows and arrows in their possession.[27] In regards to provisions, men were instructed not to eat food until a specific location was reached, and carts should carry three months worth of food and six months worth of weapons and article of clothing along with tools.[28] Preference was shown towards mobility instead of defence-in-depth infrastructures; captured fortifications were often destroyed so they could non be used to resist Carolingian potency in the future.[29] After 800 and during the reign of Louis the Pious, efforts of expansion dwindled. Tim Reuter has shown that many armed forces efforts during Louis' reign were largely defensive and in response to external threats.[25]

It had long been held that Carolingian military success was based on the utilize of a cavalry force created by Charles Martel in the 730s.[30] Nonetheless, it is clear that no such "cavalry revolution" took identify in the Carolingian period leading upward to and during the reign of Charlemagne.[31] This is because the stirrup was not known to the Franks until the late eighth century and soldiers on horseback would therefore have used swords and lances for hit and not charging.[32] Carolingian armed services success rested primarily on siege technologies and fantabulous logistics.[31] However, large numbers of horses were used past the Frankish military during the age of Charlemagne. This was considering horses provided a quick, long-distance method of transporting troops, which was critical to edifice and maintaining such a large empire.[27] The importance of horses to the Carolingian military is revealed through the Revised version of the Regal Frankish Register. The annals mention that whilst Charlemagne was on entrada in 791 "there broke out such a pestilence among the horses [...] that barely a tenth out of and so many thousands are said to take survived."[33] Shortage of horses played a role in preventing Carolingian forces from continuing a campaign against the Avars in Pannonia.[28]

Palaces [edit]

No permanent capital urban center existed in the empire, the afoot court being a typical characteristic of all Western European kingdoms at this fourth dimension. Some palaces can, however, be distinguished as locations of central administration. In the first year of his reign, Charlemagne went to Aachen (French: Aix-la-Chapelle; Italian: Aquisgrana). He began to build a palace in that location in the 780s[34] with original plans beingness thought up perhaps as before long equally 768.[34] The palace chapel, constructed in 796, later became Aachen Cathedral. During the 790s when construction picked upwardly at Aachen Charlemagne'southward courtroom became more centred compared with the 770s where court so often found itself located in tents during campaigning.[35] Though Aachen was certainly not intended to be a sedentary capital it was built in the political heartland of Charlemagne'south realm to human action as a meeting place for aristocrats and churchmen so that patronage might exist distributed, assemblies held, laws written, and even where scholarly churchmen gathered for the purposes of learning.[36] Aachen was also a centre for information and gossip being pulled in from beyond the Empire past courtiers and churchmen akin.[35] Of form, despite being the heart of Charlemagne's authorities, until his later years, his court moved often and made use of other palaces at Frankfurt, Ingelheim and Nijmegen. The employ of such structures would signal the beginnings of the palace system of government used by the Carolingian courtroom throughout reigns of many Carolingian rulers.[37] Stuart Airlie has suggested that there were over 150 palaces throughout the Carolingian Globe which would provide the setting for courtroom activity.[35]

Palaces were non merely locations of administrative government only also stood every bit of import symbols. Under Charlemagne their excellence was a translation of the treasure built upwards from conquest into a symbolic permanence as well as exclaiming royal authorization.[37] [35] Einhard suggested the construction of so-chosen 'public buildings' was a testament to Charlemagne's greatness and likeness to the emperors of antiquity and this connexion was certainly capitalised upon by the imagery of palace decorations. Ingelheim is a item example of such symbolism and thus the importance of the palace organization in more than than mere governance. The palace chapel is written to accept been 'lined with images from the Bible' and the hall of the palace 'decorated with a picture cycle jubilant the deeds of great kings' including rulers of antiquity as well as Carolingian rulers such as Charles Martel and Pippin 3.[37] [35]

Louis the Pious used the palace organisation much to the same effect as Charlemagne during his reign as king of Aquitaine, rotating his courtroom between iv winter palaces throughout the region.[37] During his reign as Emperor he used Aachen, Ingelheim, Frankfurt, and Mainz which were well-nigh e'er the locations for general assemblies held 'ii or three [times] a yr in the menses 896–28...' and while he was non an immobile ruler, his reign has certainly been described as more static.[37] In this style the palace organisation can too been seen as a tool of continuity in governance. After the splintering of the Empire the palace arrangement continued to be used by succeeding Carolingian rulers with Charles the Baldheaded centring his power at Compiègne[38] where the palace chapel was defended to the Virgin Mary in 877, something remarked on equally a sign of continuity with Aachen'south Mother of God chapel.[39] For Louis the German, Frankfurt has been deemed his ain 'neo-Aachen' and Charles the Fat's palace at Sélestat in Alsace was designed specifically to imitate Aachen.[39]

Palace System in Historiography [edit]

The palace system as an thought for Carolingian central administration and governance has been challenged by historian F. Fifty. Ganshof who argued that the palaces of the Carolingians 'contained nothing resembling the specialised services and departments bachelor at the aforementioned period to the Byzantine emperor or the caliph of Baghdad.'[twoscore] However, further reading in the works of Carolingian historians such every bit Matthew Innes, Rosamond McKitterick, and Stuart Airlie suggest that the utilize of palaces were important in the evolution of Carolingian governance and Janet Nelson has argued that 'palaces are places from which power emanates and is exercised...' and the importance of palaces to Carolingian administration, learning, and legitimacy has been widely argued.[34]

Household [edit]

The royal household was an afoot body (until c. 802) which moved around the kingdom making sure good authorities was upheld in the localities. The well-nigh important positions were the chaplain (who was responsible for all ecclesiastical affairs in the kingdom), and the count of the palace (Count palatine) who had supreme control over the household. It too included more minor officials e.g. chamberlain, seneschal, and marshal. The household sometimes led the army (e.m. Seneschal Andorf against the Bretons in 786).

Possibly associated with the clergyman and the royal chapel was the role of the chancellor, head of the chancery, a non-permanent writing office. The charters produced were rudimentary and mostly to do with land deeds. There are 262 surviving from Charles' reign as opposed to xl from Pepin's and 350 from Louis the Pious.

Officials [edit]

In that location are iii principal offices which enforced Carolingian authorisation in the localities:

The Comes (Latin: count). Appointed past Charles to administer a canton. The Carolingian Empire (except Bavaria) was divided upwards into between 110 and 600 counties, each divided into centenae which were under the control of a vicar. At first, they were royal agents sent out by Charles simply afterwards c. 802 they were of import local magnates. They were responsible for justice, enforcing capitularies, levying soldiers, receiving tolls and dues and maintaining roads and bridges. They could technically be dismissed by the male monarch but many offices became hereditary. They were as well sometimes decadent although many were exemplary e.thousand. Count Eric of Friuli. Provincial governors somewhen evolved who supervised several counts.

The Missi Dominici (Latin: dominical emissaries). Originally appointed ad hoc, a reform in 802 led to the function of missus dominicus becoming a permanent i. The Missi Dominici were sent out in pairs. Ane was an ecclesiastic and i secular. Their status as high officials was idea to safeguard them from the temptation of taking bribes. They made iv journeys a year in their local missaticum, each lasting a month, and were responsible for making the royal will and capitularies known, judging cases and occasionally raising armies.

The Vassi Dominici. These were the male monarch'due south vassals and were usually the sons of powerful men, holding 'benefices' and forming a contingent in the royal army. They likewise went on advertizement hoc missions.

Legal system [edit]

Around 780 Charlemagne reformed the local system of administering justice and created the scabini, professional experts on the law. Every count had the help of seven of these scabini, who were supposed to know every national law so that all men could be judged according to it.

Judges were also banned from taking bribes and were supposed to use sworn inquests to establish facts.

In 802, all constabulary was written down and amended (the Salic constabulary was also amended in both 798 and 802, although even Einhard admits in section 29 that this was imperfect). Judges were supposed to take a re-create of both the Salic constabulary lawmaking and the Ripuarian constabulary code.

Coinage [edit]

Coinage had a strong association with the Roman Empire, and Charlemagne took upwardly its regulation with his other imperial duties. The Carolingians exercised controls over the silver coinage of the realm, decision-making its limerick and value. The proper noun of the emperor, not of the minter, appeared on the coins. Charlemagne worked to suppress mints in northern Germany on the Baltic sea.

Subdivision [edit]

The Frankish kingdom was subdivided past Charlemagne into iii separate areas to brand administration easier. These were the inner "core" of the kingdom (Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy) which were supervised directly past the missatica system and the afoot household. Outside this was the regna where Frankish administration rested upon the counts, and outside this was the marcher areas where ruled powerful governors. These marcher lordships were present in Brittany, Espana, and Bavaria.

Charles also created two sub-kingdoms in Aquitaine and Italy, ruled by his sons Louis and Pepin respectively. Bavaria was also under the command of an autonomous governor, Gerold, until his death in 796. While Charles withal had overall authority in these areas they were fairly democratic with their own chancery and minting facilities.

Placitum generalis [edit]

The annual meeting, the Placitum Generalis or Marchfield, was held every year (betwixt March and May) at a place appointed by the male monarch. It was called for three reasons: to gather the Frankish host to go along a entrada, to hash out political and ecclesiastical matters affecting the kingdom and to legislate for them, and to brand judgments. All important men had to go to the meeting and so information technology was an important style for Charles to brand his will known. Originally the meeting worked finer however afterward it but became a forum for discussion and for nobles to express their dissatisfaction.

Oaths [edit]

The oath of fidelity was a way for Charles to ensure loyalty from all his subjects. As early as 779 he banned sworn guilds between other men so that everyone took an oath of loyalty simply to him. In 789 (in response to the 786 rebellion) he began legislating that everyone should swear allegiance to him as rex, withal in 802 he expanded the oath greatly and made it so that all men over age 12 swore information technology to him.

Capitularies [edit]

Capitularies were the written records of decisions fabricated past the Carolingian kings in consultation with assemblies during the 8th and ninth century.[41] The name comes from the Latin 'Capitula' for 'Capacity' and refers to the way these records were taken and written up, in a affiliate by chapter style. They are regarded as being 'amongst the most important sources for the governance of the Frankish Empire in the eight and ninth century' by Sören Kaschke.[42] The use of capitularies represent a change in the design of contact between the king and his provinces in the Carolingian menstruum. The contents of capitularies could include a wide range of topics, including purple orders, instructions for specific officials, deliberations of assemblies on both secular and ecclesiastical affairs too as additions and alterations to the law.

Chief show shows that capitularies were copied and disseminated all throughout Charlemagne's empire, however there is insufficient show to suggest the efficacy of the capitularies and whether they were actually put into exercise throughout the realm. As Charlemagne became increasingly stationary, the amount of capitularies produced increased, this was especially noticeable after the General Admonition of 789.

There has been debates over the purpose of capitularies. Some historians argue that the capitularies were nix more than a 'imperial wish-list' while others fence for capitularies representing the ground of a centralised land.[41] Capitularies were implemented through the use of the 'missi', imperial agents who would travel around the Carolingian kingdom, usually in pairs of a secular missi and ecclesiastical missi, reading out copied out versions of the latest capitularies to assemblies of people. The missi as well had other roles such as handling circuitous local disputes and can exist argued to have been crucial to the success of both capitularies and the expansion of Charlemagne'southward influence.

Some notable capitularies from Charlemagne's reign are:

- The Capitulary of Herstal of 779: Dealt with both ecclesiastical and secular topics, placing importance on the importance of paying Tithes, the role of the Bishop and outlining the intolerance of forming an armed following in Charlemagne's empire.

- Admonitio Generalis of 789: One of the most influential Capitularies of Charlemagne's time. Consisted of over 80 chapters, including many laws on religion.

- The Capitulary of Frankfurt of 794: Speaks out against adoptionism and iconoclasm.

- The Programmatic Capitulary of 802. This shows an increasing sense of vision in guild.

- The Capitulary for the Jews of 814, delineating the prohibitions of Jews engaging in commerce or money-lending.

Religion and the Church [edit]

Charlemagne aimed to catechumen all those in the Frankish kingdom to Christianity and to expand both his empire and the reach of Christianity. The 789 Admonitio Generalis pronounced Charlemagne responsible for the salvation of his subjects and set out standards of education for the clergy, who previously had been by and large illiterate.[43]

Intellectuals of the time began to be concerned with eschatology, assertive 800 A.D. to exist 6000 AM based on calculations from Eusebius and Jerome. Intellectuals such as Alcuin reckoned that the Charlemagne'due south coronation every bit emperor on Christmas Day 800 marked the beginning of the seventh and final age of the world.[44] These concerns may explain why Charlemagne aimed to have everyone engage in acts of penance.

Emperors [edit]

For other Carolingian kings, run into List of Frankish kings. For the later emperors, see Holy Roman Emperor.

| Proper name | Date of imperial coronation | Date of expiry | Contemporary coin or seal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charlemagne | 25 December 800 | 28 Jan 814 |  |

| Louis the Pious | 1st: eleven September 813[45] 2nd: 5 Oct 816 | 20 June 840 |  |

| Lothair I | 5 April 823 | 29 September 855 |  |

| Louis II | 1st: Easter 850 2nd: eighteen May 872 | 12 August 875 |  |

| Charles the Bald | 29 Dec 875 | six Oct 877 |  |

| Charles the Fat | 12 February 881 | 13 January 888 |  |

Legacy [edit]

Carolingian Empire superimposed over contemporary European national boundaries

Carolingians in historiography [edit]

Despite the relatively curt existence of the Carolingian Empire when compared to other European dynastic empires, its legacy far outlasts the land that had forged it. In historiographical terms, the Carolingian Empire is seen as the beginning of 'feudalism'; or rather, the notion of bullwork held in the modern era. Though most historians would exist naturally hesitant to assign Charles Martel and his descendants as founders of feudalism, it is obvious that a Carolingian 'template' lends to the structure of central medieval political culture.[46] Yet some argue confronting this assumption; Marc Bloch disdained this hunt for bullwork's nativity as 'the idol of origins'.[47] A concerted effort can be noted by Carolingian authors, such every bit Einhard, to establish a shift in continuity from the Merovingian to the Carolingian, likely where no such groundbreaking difference betwixt the ii ever existed.[46]

Symbolism of the dynasty [edit]

The unifying power of Charlemagne and his descendants have been wielded by a succession of European rulers to bolster their own regimes; much in the same vein every bit Charlemagne echoed elements of Augustus in his rising years. The Ottonian dynasty which succeeded the championship of Holy Roman Emperor magnified distant ties to the Carolingians to legitimise their dynastic ambitions as 'successors'.[46] Iv of the five Ottonian emperors to rule also crowned themselves in Charlemagne's palace in Aachen, likely to establish a continuity between the Carolingians and themselves. Fifty-fifty with their dynasty originating from Charlemagne's arch-foe Saxony, Ottonians still linked their dynasty to the Carolingians, through direct and indirect ways.[48] Further iconography of Charlemagne himself was utilised in later on medieval periods, where he is depicted as a model knight and paragon of knightly.

See likewise [edit]

- Carolingian Renaissance

- Carolingian architecture

- Carolingian art

- List of Carolingian monasteries

Notes [edit]

- ^ Sometimes with Romanum (Roman) replacing Romanorum (of the Romans) and atque (and) replacing sive (or).

- ^ An unknown anonymous author, see Vita Hludovici

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b McKitterick 2008, p. 23.

- ^ a b c McCormick, Michael (2007). "Where exercise trading towns come from? Early medieval Venice and the northern emporia". In Henning, Joachim (ed.). Post-Roman towns, trade and settlement in Europe and Byzantium. p. 50. ISBN978-iii-eleven-018356-6.

Overall population estimates for the Carolingian empire range today from ten to twenty meg, including the Italian territories. The size of the Carolingian empire can be roughly estimated at ane,112,000 km2

- ^ Garipzanov, Ildar H. (2008). The Symbolic Language of Authority in the Carolingian World (c.751–877). ISBN9789047433408.

- ^ a b Magill, Frank (1998). Dictionary of Earth Biography: The Middle Ages, Book 2. Routledge. pp. 228, 243. ISBN978-1579580414.

- ^ Davis, Jennifer (2015). Charlemagne'southward Do of Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN978-1316368596.

- ^ Joanna Story, Charlemagne: Empire and Club, Manchester University Printing, 2005 ISBN 978-0-7190-7089-one

- ^ a b c Kramer, Rutger (2019). Rethinking Authorisation in the Carolingian Empire: Ideals and Expectations During the Reign of Louis the Pious (813-828). pp. 31–34. ISBN9789048532681.

- ^ Ernold. Carmen. Vol. lib. I, 11, 85–91. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Astronumus (the Astronomer). "Chapter 19". Vita Hludowici. p. 336.

- ^ a b c d e f m De Jong, Mayke (2009). The Penitential Country: Authority and Atonement in the Age of Louis the Pious, 814-840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. pp. 20–47.

- ^ "Defection of Bernard of Italian republic", The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1-v, Plantagenet Publishing

- ^ McKitterick, Rosamond (1983). The Frankish kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. ISBN9780582490055.

- ^ Knechtges, David R.; Vance, Eugene (2005). Rhetoric and the Discourses of Power in Courtroom Culture. ISBN9780295984506.

- ^ The Astronomer (anonymous) (2009). "The Life of Emperor Louis". Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer. Translated by Thomas F. X. Noble. p. 275. ISBN9780271037158.

- ^ "Die Geburt Zweier Staaten – Die Straßburger Eide vom 14. February 842 | Wir Europäer | DW.DE | 21.07.2009". Dw-world.de. 2009-07-21. Retrieved 2013-03-26 .

- ^ Goldberg, Eric Joseph (2006). Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict Nether Louis the German, 817–876. ISBN978-0-8014-3890-5.

- ^ MacLean, Simon (2003). Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fatty and the End of the Carolingian Empire. ISBN978-0-521-81945-9.

- ^ a b Wickham, Chris (2005-09-22). Framing the Early Middle Ages. Oxford University Press. p. 674. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199264490.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-926449-0.

- ^ Schroeder, Nicholas (2019). "Observations about Climate, Farming, and Peasant Societies in Carolingian Europe". The Journal of European Economic History. 3: 189–210.

- ^ Henning, Joachim, ed. (2007). "Where exercise trading towns come from? Early on medieval Venice and the northern emporia". Postal service-Roman Towns, Merchandise and Settlement in Europe and Byzantium: The heirs of the Roman West. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 41–61. ISBN978-3110183566.

- ^ Newfield, Timothy (2013). "The Contours, Frequency and Causation of Subsistence Crises in Carolingian Europe (750–950)". In I Monclús, Pere Benito (ed.). Crunch Alimentarias en la Edad Media: Modelos, Explicaciones y Representaciones. Lleida: editorial Milenio. pp. 117–172. ISBN978-84-9743-491-1.

- ^ McCormick, Michael; Dutton, Paul Edward; Mayewski, Paul A. (2007). "Volcanoes and the Climate Forcing of Carolingian Europe, A.D. 750-950" (PDF). Speculum. 82 (4): 865–895. doi:ten.1017/S0038713400011325. S2CID 154776670.

- ^ Walter, Pohl (2017). "Ethnicity in the Carolingian Empire". In Tor, D. 1000. (ed.). The 'Abassid and Carolingian Empires: Comparative Studies in Civilisational Formation. Netherlands: BRILL. pp. 102–117. ISBN978-9004353046.

- ^ Kowaleski, Maryanne (2013). "Gendering Demographic Change in the Eye Ages". In Benett, Judith Thousand.; Karras, Ruth Mazo (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe (First ed.). pp. 181–192. ISBN978-0-19-958217-iv. OCLC 829743917.

- ^ a b Reuter 2006, p. 252.

- ^ Hooper & Bennett 1996, p. 13.

- ^ a b Hooper & Bennett 1996, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Hooper & Bennett 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Bowlus 2006, p. 49.

- ^ Hooper & Bennett 1996, p. 12.

- ^ a b Bowlus 2006, p. 49.

- ^ Hooper & Bennett 1996, pp. 12–13.

- ^ King, P. D. (1987). Charlemagne Translated Sources. p. 124. ISBN978-0951150306.

- ^ a b c Nelson, Janet (2019). King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne. London: Allen Lane. pp. 232, 356.

- ^ a b c d e Airlie, Stuart (2012). Power and Its Bug in Carolingian Europe. Ashgate. pp. iv–xi.

- ^ Innes, Matthew (2005). "Charlemagne's Regime". In Story, Joanna (ed.). Charlemagne: Empire and Lodge. Manchester University Printing. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Costambeys 2011, pp. 173–177.

- ^ McKitterick 1983, p. 22.

- ^ a b Costambeys 2011, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Ganshof, F. L. (1971). The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy. Translated past Sondheimer, Janet. Longman. p. 257.

- ^ a b Charlemagne : empire and society. Story, Joanna, 1970-. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 2005. ISBN0-7190-7088-0. OCLC 57062144.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kaschke, Sören; Mischke, Britta (2019). "Capitularies in the Carolingian Flow". History Compass. 17 (10). doi:10.1111/hic3.12592. ISSN 1478-0542. S2CID 203080653.

- ^ Charlemagne : translated sources. Rex, P. D. Lambrigg, Kendal, Cumbria: P.D. Rex. 1987. ISBN0-9511503-0-8. OCLC 21517645.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Story, Joanna (2005). Charlemagne: Empire and Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 105. ISBN978-0-7190-7089-i.

- ^ Egon Boshof: Ludwig der Fromme. Darmstadt 1996, p. 89

- ^ a b c Costambeys 2011, pp. 428–435.

- ^ Bloch, Marc (1992). The Historian'south Craft, ed. P. Shush. Manchester. pp. 24–29.

- ^ "The paradox of the by in the crunch of the Carolingian Empire – After Empire". arts.st-andrews.ac.uk . Retrieved 2020-02-17 .

References [edit]

- Bowlus, Charles R. (2006). The Battle of Lechfeld and its Backwash, August 955: The End of the Historic period of Migrations in the Latin West. ISBN978-0-7546-5470-iv.

- Chandler, Tertius; Play a joke on, Gerald (1974). 3000 Years of Urban Growth . New York and London: Academic Press. ISBN9780127851099.

- Costambeys, Mario (2011). The Carolingian World. ISBN9780521563666.

- Hooper, Nicholas; Bennett, Matthew (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: the Middle Ages. ISBN978-0-521-44049-three.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (2008). Charlemagne: the formation of a European identity. England. ISBN978-0-521-88672-7.

- Reuter, Timothy (2006). Medieval Polities and Modernistic Mentalities. ISBN9781139459549.

External links [edit]

- The Making of Charlemagne'south Europe (768–814) (freely available database of prosopographical and socio-economical data from Carolingian legal documents, produced and maintained past King's College London)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolingian_Empire

0 Response to "what happened to the frankish empire after charlemagne died"

Post a Comment